Elephant grass is an alternative to generate thermoelectric power and replace firewood The name of the current biggest land animal fits elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum) like a glove. The plant reaches the height of four meters just six months after sowing. With an African origin, it was introduced in Brazil in the late 1920s and is grown throughout the country, mainly in forage grass systems. Picked and chopped, it is offered as food to livestock, usually during the winter, when drought and cold leave animals without pastures. But such a production volume has also arisen the interest of another field: energy. Elephant grass can supply biomass that, as it is burned, generates energy and steam that drives turbines and triggers generators. This is what Sykué Bioenergya, in São Desidério, Bahia, is doing, adding energy in the Brazilian transmission network. In the state of Goiás, some red ceramic industries, as an experiment, have used grass instead of wood in the ovens. The elephant grass can also become ecological firewood through a compression process that turns it into briquettes or pellets. Finally, it serves as raw material for cellulosic ethanol, known as 2nd generation (2G) ethanol. Like any plant, from its cellulose one can extract sugars, that, when fermented, originate biofuel that can fuel cars and even airplanes. The background for the effort of institutions and companies in the development of technology of cultivation and processing of elephant grass for energy is the pressure for the adoption of less impactful solutions from an environmental point of view. The Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP-20), held in Peru in December 2014, pointed out the need for a 40% to 70% reduction of GHG emissions by 2050, so as not to exceed the 2°C increase of average temperatures in the planet by the end of this century. The use of clean energy, such as from the use of elephant grass biomass, is on the list of investigated alternatives. According to the researcher José Dilcio Rocha, from Embrapa Agroenergy, the insertion of elephant grass in the national energy network has a strategic role. First, this grass can be a tool for the decentralization of production, allowing the generation of electricity and the production of bioenergy in places where the construction of dams or traditional biomass cultivation is not possible. The Brazilian Ministry of Mines and Energy forecasts the need to increase the installed capacity of power generation in Brazil from the current 124.8 GW to 195.9 GW until 2023. "Sometimes the solution you need is not national, but regional", says Rocha. Production for years to come Various other plants, such as sugarcane and eucalyptus, are already or may be used for those applications. Then, why invest in elephant grass? High productivity is the first answer. The Embrapa Coastal Tablelands researcher Anderson Marafon says that, with two annual harvests, between 150 and 200 tons of fresh mass are drawn per cultivated hectare, which yields from 40 to 50 tons of dry mass. Studies show that, if the goal is to produce biomass for energy, the first harvest of elephant grass can be done six months after planting. For sugarcane, this period is three times longer and, for eucalyptus, it goes as far as seven years. In addition, elephant grass is a perennial species. If and only if it is well managed, a cultivated area with the grass can continue re-sprouting for many years. The possibility of mechanization of the harvest and maintenance of a continuous flow of raw materials throughout the year are other advantages pointed out. In the production of bricks, tiles, and other red ceramic products, some companies are beginning to experiment with replacing wood by elephant grass in the ovens. The Center of Alternative Renewable Energies of the government of Goiás is investing in the grass as biomass to supply the sector with energy, avoiding middlemen in the purchase of firewood and preventing the use of native wood. The Center's development manager, Victor Salomão de Pina, tells that a project to promote the use of raw materials, especially in the area of Anápolis, is under development. "The main challenge is to dominate the production chain and the lack of technical knowledge of those who want to use it", he comments. Elephant grass could also broaden the participation and diversify renewable energy sources in Brazil. Increasingly driven by prolonged periods of drought, the generating capacity in thermal units today is little more than 39 million kW, according to data from the Brazil's National Electric Energy Agency (Aneel). Out of this volume, little more than 30% come from biomass. The remainder is fueled by fossil products, especially diesel oil and mineral coal. Among those that use biomass, there is a prevalence of the use of bagasse – which mainly supplies the very own sugar mills that produce it with energy– and wood waste. Elephant grass already appears as fuel to two companies: one in Amapá and another in Bahia. The latter is the most emblematic experience of the use of elephant grass for energy purposes in Brazil. With an installed capacity of 30 million kW, Sykué Bioenergya began to put the project of transforming this grass into electricity into practice three years ago, when the first seedlings were planted in São Desidério, Bahia. The project coordinator, Giovanna Rajoy, and the Sykué CEO, Carlos Taparelli, reveal that many difficulties are being encountered in the pioneering initiative. Inadequate seedlings, productivity that is lower than expected, high humidity and need for investment to be higher than initially planned are among the problems. Is there any firm intention to expand the use of elephant grass for energy generation? The decision will only be taken after a few years of experimentation. Giovanna and Taparelli understand that knowing the production cycle better and establishing technological routes for other uses of the grass – ethanol, for example – are among the needs. The vice-president of technology and development of Dedini Indústrias de Base, in Piracicaba, São Paulo, José Luiz Olivério, reinforces that knowing the biomass that serves as fuel well is the most important factor for the good performance of a thermal project. "The wealth from the sugarcane is produced in the fields; the power plant has the role of not losing what the field produced", he informs. The company located in inner São Paulo was responsible for planning and assembling Sykué's industrial plant. "That really excited us because it was an unprecedented challenge; at that time, no other facility known to produce electric energy from the elephant grass existed", says Olivério. The main restraint was the design of the structure for receiving, storing, processing and transporting the biomass to the furnaces. From that point, the project is quite similar to those already used for the burning of sugarcane bagasse. In the field The challenges identified in São Desidério are subject of research being developed in an integrated way in various Embrapa Units to give the sector the answers that it needs. Currently, the grass is grown in small areas, using varieties and production systems that have the production of forage as target. The difference begins at the composition of the desired material. To feed the cattle, what is desirable is a protein-rich biomass that has, therefore, a low carbon/nitrogen ratio. When the goal is to use the material as fuel, what is sought is the exact opposite. "This result was achieved only with management, increasing the range of cutting and reducing nitrogen fertilization", explains the researcher Francisco Ledo, from Embrapa Dairy Cattle (MG). In this Unit lies the corporation's elephant grass Active Germplasm Bank, comprising 120 varieties. Embrapa's first step towards using elephant grass as biomass for energy purposes has been the assessment of varieties available to identify the most suitable one. The researcher Antônio Vander Pereira, from Embrapa Dairy Cattle, clarifies that, although the development of specific varieties for this application is on the horizon of the work, there is no need to wait years for it. "The materials that we already have are highly productive and suitable for the energy production", he guarantees. Soon, technical recommendations should be released accordingly. Actions for genetic improvement have also already started. With a project inserted at Embrapa's portfolio for the sugar-energy sector, the gene bank's accessions are being reassessed, seeking materials with desirable characteristics for future programs to obtain cultivars. "Our intention is to generate resources for the implementation of a specific project for power generation with elephant grass", says the project leader Juarez Campolina Machado. There is a network of research institutions participating in the tests, in four regions of the country: South, Southeast, Midwest and Northeast. Embrapa Agroenergy is one of the Units that participates in this project, characterizing the biomass of pre-selected accessions, in partnership with the Multi-user Laboratory of Chemistry of Natural Products of Embrapa Tropical Agroindustry, Ceará. Using nuclear magnetic resonance, not only the composition is being investigated, but also the chemical structure of materials. Researcher Patricia Abrão, from Brasília, explains that knowing the levels of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin is not enough to understand why a sample has better results than another in the ethanol production process, for instance. Finding out what the monomers that make up each of these structures are and the links between them informs the work of the breeders. At Embrapa, there are also studies in which accessions from the gene bank are being genetically crossed, seeking materials with desirable characteristics for energy purposes. The goal is to obtain more productive new varieties, tolerant to pests and diseases and adapted to the different Brazilian regions. Large areas Another challenge is the development of production systems in large tracts of land. For the researcher Letícia Jungmann, from Embrapa Agroenergy, this is one of the main limitations, including harvest and post-harvest systems. Currently, elephant grass is grown as grass crops that take up small areas. When thinking of ethanol production or generation of bioelectricity, however, there is a need for a lot of material. Sykué has used 5,000 hectares to grow the grass; on its website, Florida Clean Power announced 500,000 hectares in Amapá for the same purpose. Pereira recalls that growing in extensive areas need appropriate management to deal, for example, with plant-health problems. It is also strategic for materials with additional cycles, with harvests at different times, to ensure dry matter production flow the whole year. In Embrapa Coastal Tablelands' Research and Development Unit in Rio Largo (AL), research involving the elephant grass production system is intended to provide an alternative source of biomass for the generation of bioelectricity in sugar and ethanol plants off season. In Alagoas, 25 plants process sugarcane and burn the bagasse to generate electric power. The researcher Anderson Marafon highlighted two issues in the final step of the elephant grass energy production system: harvesting and reducing humidity. Two methods of sun drying are being tested: with the grass just cut and "laid" in the field, or with the material chopped and placed in the yard of the power plant. The latter has managed to lower 70% to 50% of the humidity after the fourth or fifth day of sun exposure.. Concerning the harvest, Embrapa's tests seek efficient machinery. In the pastures, the material is harvested young and tender, a condition that is more suitable for animal feeding. To produce biomass for energy, the plant has to remain for about six months in the field. The grass, then, is more fibrous and tough and the typically used harvesters are not strong enough. Grass ethanol While the team searches solutions for the improvement of crop production, in the laboratories of Embrapa Agroenergy, elephant grass is a raw material that has been tested for the production of cellulosic ethanol (2G) since 2009. The experiments began with the participation in a project led by researcher Marcelo Ayres, from Embrapa Cerrados (DF), to identify alternative sources of biomass for sustainable biofuel production. In this study, elephant grass was compared with other forage plants, sorghum, wood and sugarcane bagasse, among other plants with energy potential. The researcher Silvia Belém from Embrapa Agroenergy claims that the elephant grass has adapted very well to the process, showing favorable characteristics. The glucose volume recovered was high, with the use of smaller quantities of enzymes. The results of this first experience made the research center choose this grass, as well as sugarcane bagasse, as raw material for a large project that is studying ways to optimize all phases of (2G) ethanol production. Bacteria and ashes to increase production The first studies Embrapa has undertaken with genotypes of elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum) for biomass production with energetic purposes began in 1995, with a team led by researcher Johanna Döbereiner (1924 - 2000) at Embrapa Agrobiology. The multidisciplinary project involved other institutions and aimed at the development of a technology for the coal production to be used in the steel industry. Embrapa then identified the most appropriate varieties. "We evaluated more than 40 genotypes in soils that were extremely poor in nitrogen because we wanted a grass that, besides producing biomass, did not need much nitrogen fertilizer," explains the researcher Segundo Urquiaga. Usually, when elephant grass is produced for livestock feed, it is necessary to use nitrogen fertilizers aiming at a plant with high protein levels, which is not necessary for biomass production. In the field, the researchers initially studied the behavior of plants in poor soils, selected those that demanded less fertilizer and then began to search for bacteria associated with elephant grass. "Using isotopic techniques, we were able to distinguish in the plant how much nitrogen came from the soil and how much came from the air through the bacteria naturally associated to it", says the researcher. If the objective is to obtain a plant for biomass production that shall be used as an alternative to fossil fuels, using agricultural inputs that require a high level of non-renewable energy, like nitrogen fertilizers, for instance, would be a contradiction. The goal, after all, was to produce grass with environmental and economic sustainability. To this end, researchers from Embrapa Agrobiology also have searched different ways to increase grass production. Ashes One of the ongoing studies uses the ash derived from burning biomass as a source of nutrients for grass crops. According to Urquiaga, experiments with ashes from furnaces of potteries – in Campos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – proved to be a material as good One of the ongoing studies uses the ash derived from burning biomass as a source of nutrients for grass crops. According to Urquiaga, experiments with ashes from furnaces of potteries – in Campos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – proved to be a material as good. A busca por variedades de capim-elefante mais eficientes em Fixação Biológica de Nitrogênio sempre esteve presente nas pesquisas. Dos quarenta genótipos avaliados inicialmente, seis são apontados pelos pesquisadores como mais tolerantes a solos pobres e dispensam grandes quantidades de adubos nitrogenados. "Hoje, sabe-se que de 35% a 40% do nitrogênio contido nas variedades mais eficientes para a produção de biomassa vem do ar, ou seja, da FBN", enfatiza Urquiaga. The search for elephant grass varieties that are more efficient regarding biological nitrogen fixation has always been present in the studies. From the forty genotypes initially evaluated, six were pointed out by the researchers as more tolerant to poor soils and did not require large amounts of nitrogen fertilizers. "Today, it is known that 35 to 40% of the nitrogen in the more efficient varieties for biomass production comes from the air, that is, from biological nitrogen fixation", emphasizes Urquiaga. Large scale For the researcher Segundo Urquiaga, agronomic issues concerning the production of grass for energetic purposes are virtually resolved, and only some adjustments to production sites are still necessary. But he highlights that large scale production is a difficult process. "We do not have sementes e isso dificulta a produção em áreas extensas", diz. Elephant grass spreads through vegetative multiplication, like sugarcane. To plant one hectare of the grass, six to eight tons of culms are necessary. If well managed, the production takes about 90 days and is enough to plant ten hectares. And for another 90 days, they could meet the needs of a hundred hectares. Considering this proportion, to reach the necessary to plant in 1,000 hectares, over one year is required. Urquiaga believes that the production of seeds is the solution to this problem. In this sense, an ongoing project at Embrapa Beef Cattle seeks to obtain a hybrid variety to produce botanical seeds to enable the planting of the grass. "This will definitely solve the problem of planting in large areas", he concludes. •

Elephant grass is an alternative to generate thermoelectric power and replace firewood

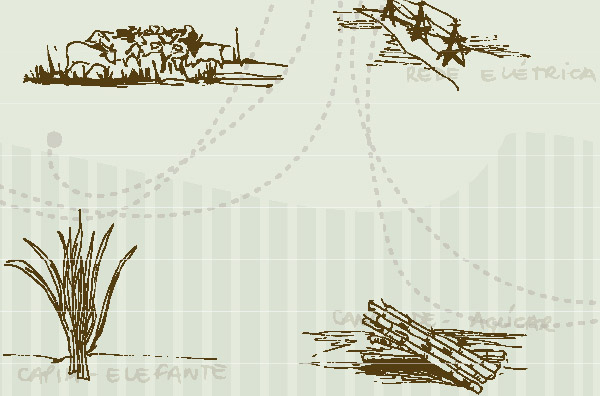

The name of the current biggest land animal fits elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum) like a glove. The plant reaches the height of four meters just six months after sowing. With an African origin, it was introduced in Brazil in the late 1920s and is grown throughout the country, mainly in forage grass systems. Picked and chopped, it is offered as food to livestock, usually during the winter, when drought and cold leave animals without pastures. But such a production volume has also arisen the interest of another field: energy.

Elephant grass can supply biomass that, as it is burned, generates energy and steam that drives turbines and triggers generators. This is what Sykué Bioenergya, in São Desidério, Bahia, is doing, adding energy in the Brazilian transmission network. In the state of Goiás, some red ceramic industries, as an experiment, have used grass instead of wood in the ovens. The elephant grass can also become ecological firewood through a compression process that turns it into briquettes or pellets. Finally, it serves as raw material for cellulosic ethanol, known as 2nd generation (2G) ethanol. Like any plant, from its cellulose one can extract sugars, that, when fermented, originate biofuel that can fuel cars and even airplanes.

The background for the effort of institutions and companies in the development of technology of cultivation and processing of elephant grass for energy is the pressure for the adoption of less impactful solutions from an environmental point of view. The Conference of the Parties on Climate Change (COP-20), held in Peru in December 2014, pointed out the need for a 40% to 70% reduction of GHG emissions by 2050, so as not to exceed the 2°C increase of average temperatures in the planet by the end of this century. The use of clean energy, such as from the use of elephant grass biomass, is on the list of investigated alternatives.

According to the researcher José Dilcio Rocha, from Embrapa Agroenergy, the insertion of elephant grass in the national energy network has a strategic role. First, this grass can be a tool for the decentralization of production, allowing the generation of electricity and the production of bioenergy in places where the construction of dams or traditional biomass cultivation is not possible. The Brazilian Ministry of Mines and Energy forecasts the need to increase the installed capacity of power generation in Brazil from the current 124.8 GW to 195.9 GW until 2023. "Sometimes the solution you need is not national, but regional", says Rocha.

Production for years to come

Various other plants, such as sugarcane and eucalyptus, are already or may be used for those applications. Then, why invest in elephant grass? High productivity is the first answer. The Embrapa Coastal Tablelands researcher Anderson Marafon says that, with two annual harvests, between 150 and 200 tons of fresh mass are drawn per cultivated hectare, which yields from 40 to 50 tons of dry mass.

Studies show that, if the goal is to produce biomass for energy, the first harvest of elephant grass can be done six months after planting. For sugarcane, this period is three times longer and, for eucalyptus, it goes as far as seven years. In addition, elephant grass is a perennial species. If and only if it is well managed, a cultivated area with the grass can continue re-sprouting for many years. The possibility of mechanization of the harvest and maintenance of a continuous flow of raw materials throughout the year are other advantages pointed out.

In the production of bricks, tiles, and other red ceramic products, some companies are beginning to experiment with replacing wood by elephant grass in the ovens. The Center of Alternative Renewable Energies of the government of Goiás is investing in the grass as biomass to supply the sector with energy, avoiding middlemen in the purchase of firewood and preventing the use of native wood. The Center's development manager, Victor Salomão de Pina, tells that a project to promote the use of raw materials, especially in the area of Anápolis, is under development. "The main challenge is to dominate the production chain and the lack of technical knowledge of those who want to use it", he comments.

Elephant grass could also broaden the participation and diversify renewable energy sources in Brazil. Increasingly driven by prolonged periods of drought, the generating capacity in thermal units today is little more than 39 million kW, according to data from the Brazil's National Electric Energy Agency (Aneel). Out of this volume, little more than 30% come from biomass. The remainder is fueled by fossil products, especially diesel oil and mineral coal.

Among those that use biomass, there is a prevalence of the use of bagasse – which mainly supplies the very own sugar mills that produce it with energy– and wood waste. Elephant grass already appears as fuel to two companies: one in Amapá and another in Bahia. The latter is the most emblematic experience of the use of elephant grass for energy purposes in Brazil. With an installed capacity of 30 million kW, Sykué Bioenergya began to put the project of transforming this grass into electricity into practice three years ago, when the first seedlings were planted in São Desidério, Bahia.

The project coordinator, Giovanna Rajoy, and the Sykué CEO, Carlos Taparelli, reveal that many difficulties are being encountered in the pioneering initiative. Inadequate seedlings, productivity that is lower than expected, high humidity and need for investment to be higher than initially planned are among the problems. Is there any firm intention to expand the use of elephant grass for energy generation? The decision will only be taken after a few years of experimentation.

Giovanna and Taparelli understand that knowing the production cycle better and establishing technological routes for other uses of the grass – ethanol, for example – are among the needs. The vice-president of technology and development of Dedini Indústrias de Base, in Piracicaba, São Paulo, José Luiz Olivério, reinforces that knowing the biomass that serves as fuel well is the most important factor for the good performance of a thermal project. "The wealth from the sugarcane is produced in the fields; the power plant has the role of not losing what the field produced", he informs.

The company located in inner São Paulo was responsible for planning and assembling Sykué's industrial plant. "That really excited us because it was an unprecedented challenge; at that time, no other facility known to produce electric energy from the elephant grass existed", says Olivério. The main restraint was the design of the structure for receiving, storing, processing and transporting the biomass to the furnaces. From that point, the project is quite similar to those already used for the burning of sugarcane bagasse.

In the field

The challenges identified in São Desidério are subject of research being developed in an integrated way in various Embrapa Units to give the sector the answers that it needs. Currently, the grass is grown in small areas, using varieties and production systems that have the production of forage as target.

The difference begins at the composition of the desired material. To feed the cattle, what is desirable is a protein-rich biomass that has, therefore, a low carbon/nitrogen ratio. When the goal is to use the material as fuel, what is sought is the exact opposite. "This result was achieved only with management, increasing the range of cutting and reducing nitrogen fertilization", explains the researcher Francisco Ledo, from Embrapa Dairy Cattle (MG). In this Unit lies the corporation's elephant grass Active Germplasm Bank, comprising 120 varieties.

Embrapa's first step towards using elephant grass as biomass for energy purposes has been the assessment of varieties available to identify the most suitable one. The researcher Antônio Vander Pereira, from Embrapa Dairy Cattle, clarifies that, although the development of specific varieties for this application is on the horizon of the work, there is no need to wait years for it. "The materials that we already have are highly productive and suitable for the energy production", he guarantees. Soon, technical recommendations should be released accordingly.

Actions for genetic improvement have also already started. With a project inserted at Embrapa's portfolio for the sugar-energy sector, the gene bank's accessions are being reassessed, seeking materials with desirable characteristics for future programs to obtain cultivars. "Our intention is to generate resources

for the implementation of a specific project for power generation with elephant grass", says the project leader Juarez Campolina Machado. There is a network of research institutions participating in the tests, in four regions of the country: South, Southeast, Midwest and Northeast.

Embrapa Agroenergy is one of the Units that participates in this project, characterizing the biomass of pre-selected accessions, in partnership with the Multi-user Laboratory of Chemistry of Natural Products of Embrapa Tropical Agroindustry, Ceará. Using nuclear magnetic resonance, not only the composition is being investigated, but also the chemical structure of materials. Researcher Patricia Abrão, from Brasília, explains that knowing the levels of cellulose, hemicellulose and lignin is not enough to understand why a sample has better results than another in the ethanol production process, for instance. Finding out what the monomers that make up each of these structures are and the links between them informs the work of the breeders.

At Embrapa, there are also studies in which accessions from the gene bank are being genetically crossed, seeking materials with desirable characteristics for energy purposes. The goal is to obtain more productive new varieties, tolerant to pests and diseases and adapted to the different Brazilian regions.

Large areas

Another challenge is the development of production systems in large tracts of land. For the researcher Letícia Jungmann, from Embrapa Agroenergy, this is one of the main limitations, including harvest and post-harvest systems. Currently, elephant grass is grown as grass crops that take up small areas. When thinking of ethanol production or generation of bioelectricity, however, there is a need for a lot of material. Sykué has used 5,000 hectares to grow the grass; on its website, Florida Clean Power announced 500,000 hectares in Amapá for the same purpose.

Pereira recalls that growing in extensive areas need appropriate management to deal, for example, with plant-health problems. It is also strategic for materials with additional cycles, with harvests at different times, to ensure dry matter production flow the whole year.

In Embrapa Coastal Tablelands' Research and Development Unit in Rio Largo (AL), research involving the elephant grass production system is intended to provide an alternative source of biomass for the generation of bioelectricity in sugar and ethanol plants off season. In Alagoas, 25 plants process sugarcane and burn the bagasse to generate electric power.

The researcher Anderson Marafon highlighted two issues in the final step of the elephant grass energy production system: harvesting and reducing humidity. Two methods of sun drying are being tested: with the grass just cut and "laid" in the field, or with the material chopped and placed in the yard of the power plant. The latter has managed to lower 70% to 50% of the humidity after the fourth or fifth day of sun exposure..

Concerning the harvest, Embrapa's tests seek efficient machinery. In the pastures, the material is harvested young and tender, a condition that is more suitable for animal feeding. To produce biomass for energy, the plant has to remain for about six months in the field. The grass, then, is more fibrous and tough and the typically used harvesters are not strong enough.

Grass ethanol

While the team searches solutions for the improvement of crop production, in the laboratories of Embrapa Agroenergy, elephant grass is a raw material that has been tested for the production of cellulosic ethanol (2G) since 2009. The experiments began with the participation in a project led by researcher Marcelo Ayres, from Embrapa Cerrados (DF), to identify alternative sources of biomass for sustainable biofuel production. In this study, elephant grass was compared with other forage plants, sorghum, wood and sugarcane bagasse, among other plants with energy potential.

The researcher Silvia Belém from Embrapa Agroenergy claims that the elephant grass has adapted very well to the process, showing favorable characteristics. The glucose volume recovered was high, with the use of smaller quantities of enzymes. The results of this first experience made the research center choose this grass, as well as sugarcane bagasse, as raw material for a large project that is studying ways to optimize all phases of (2G) ethanol production.

Bacteria and ashes to increase production

The first studies Embrapa has undertaken with genotypes of elephant grass (Pennisetum purpureum) for biomass production with energetic purposes began in 1995, with a team led by researcher Johanna Döbereiner (1924 - 2000) at Embrapa Agrobiology. The multidisciplinary project involved other institutions and aimed at the development of a technology for the coal production to be used in the steel industry. Embrapa then identified the most appropriate varieties. "We evaluated more than 40 genotypes in soils that were extremely poor in nitrogen because we wanted a grass that, besides producing biomass, did not need much nitrogen fertilizer," explains the researcher Segundo Urquiaga.

Usually, when elephant grass is produced for livestock feed, it is necessary to use nitrogen fertilizers aiming at a plant with high protein levels, which is not necessary for biomass production. In the field, the researchers initially studied the behavior of plants in poor soils, selected those that demanded less fertilizer and then began to search for bacteria associated with elephant grass. "Using isotopic techniques, we were able to distinguish in the plant how much nitrogen came from the soil and how much came from the air through the bacteria naturally associated to it", says the researcher.

If the objective is to obtain a plant for biomass production that shall be used as an alternative to fossil fuels, using agricultural inputs that require a high level of non-renewable energy, like nitrogen fertilizers, for instance, would be a contradiction. The goal, after all, was to produce grass with environmental and economic sustainability. To this end, researchers from Embrapa Agrobiology also have searched different ways to increase grass production.

Ashes

One of the ongoing studies uses the ash derived from burning biomass as a source of nutrients for grass crops. According to Urquiaga, experiments with ashes from furnaces of potteries – in Campos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – proved to be a material as good One of the ongoing studies uses the ash derived from burning biomass as a source of nutrients for grass crops. According to Urquiaga, experiments with ashes from furnaces of potteries – in Campos, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – proved to be a material as good.

A busca por variedades de capim-elefante mais eficientes em Fixação Biológica de Nitrogênio sempre esteve presente nas pesquisas. Dos quarenta genótipos avaliados inicialmente, seis são apontados pelos pesquisadores como mais tolerantes a solos pobres e dispensam grandes quantidades de adubos nitrogenados. "Hoje, sabe-se que de 35% a 40% do nitrogênio contido nas variedades mais eficientes para a produção de biomassa vem do ar, ou seja, da FBN", enfatiza Urquiaga.

The search for elephant grass varieties that are more efficient regarding biological nitrogen fixation has always been present in the studies. From the forty genotypes initially evaluated, six were pointed out by the researchers as more tolerant to poor soils and did not require large amounts of nitrogen fertilizers.

"Today, it is known that 35 to 40% of the nitrogen in the more efficient varieties for biomass production

comes from the air, that is, from biological nitrogen fixation", emphasizes Urquiaga.

Large scale

For the researcher Segundo Urquiaga, agronomic issues concerning the production of grass for energetic purposes are virtually resolved, and only some adjustments to production sites are still necessary. But he highlights that large scale production is a difficult process. "We do not have sementes e isso dificulta a produção em áreas extensas", diz.

Elephant grass spreads through vegetative multiplication, like sugarcane. To plant one hectare of the grass, six to eight tons of culms are necessary. If well managed, the production takes about 90 days and is enough to plant ten hectares. And for another 90 days, they could meet the needs of a hundred hectares. Considering this proportion, to reach the necessary to plant in 1,000 hectares, over one year is required.

Urquiaga believes that the production of seeds is the solution to this problem. In this sense, an ongoing project at Embrapa Beef Cattle seeks to obtain a hybrid variety to produce botanical seeds to enable the planting of the grass. "This will definitely solve the problem of planting in large areas", he concludes. •