Climate change has blast reduce global wheat production by 13%

Climate change has blast reduce global wheat production by 13%

Photo: Flávio Martins Santana

Wheat blast has the potential to affect 13.5 million hectares and risk of reducing world wheat production by 13%

|

Climate change is conducive to the fungus that causes blast, a disease that has significant impacts on wheat production. It has the potential to affect 13.5 million hectares and risks reducing global wheat production by 13%. The projections are from the study Production vulnerability to wheat blast disease under climate change published on Nature Climate Change.

Wheat blast is considered the most recently identified disease of economic importance for the crop in the world. It is caused by a fungus, the Pyricularia oryzae Triticum (Magnaporthe oryzae pathotype Triticum), which attacks leaves and ears, causing damage that can compromise up to 100% of the wheat yield.

According to the Embrapa Wheat researcher José Maurício Fernandes, the development of the fungus that causes blast is favored by high temperatures and humidity, conditions that are present in countries with tropical and subtropical climates. According to him, the incidence of the disease in cold weather conditions or even low humidity has drawn attention.

In recent years, crops with blast have been observed in northern Bangladesh, where the fungus has survived the dry weather and low temperatures during the wheat harvest, especially as minimum temperatures have risen in recent years.

The higher temperatures in the winter in Southern Brazil have also resulted in localized blast outbreaks in the 2023 wheat harvest in Rio Grande do Sul, especially in the northwestern portion of the state, where minimum temperatures were above 15 ºC throughout the harvest season. “In a scenario of global climate change, with higher temperatures and variation in rainfall, the fungus will find new environments to settle”, the researcher predicts, as he recalls that fungus spores can be dispersed through the wind or the international trade of contaminated grains and seeds.

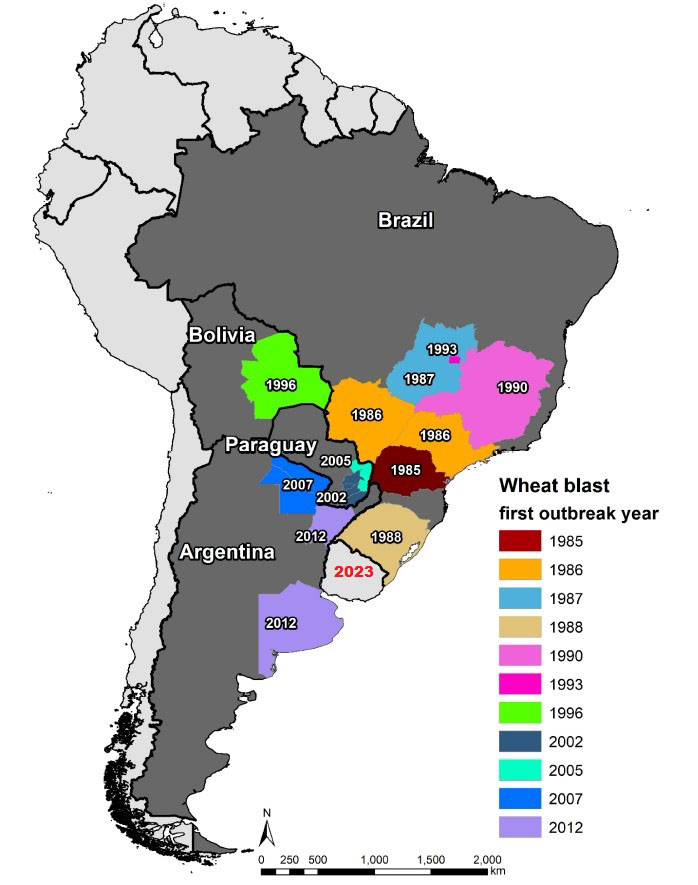

A fungus that attacks cerealsThe fungus is an old acquaintance of rice crops, as the first reports of rice blast date back to the 1600s in China. In wheat, the microorganism that causes blast was identified for the first time in Brazil in 1985, in wheat fields in the state of Paraná, but the disease quickly spread to other Brazilian states (Mato Grosso do Sul, São Paulo, Goiás and Minas Gerais ), in addition to different countries in South America. See the spread of blast in South America on the map below: From Wheat Blast: A Disease Spreading by Intercontinental Jumps and Its Management Strategies

According to information from the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT), blast epidemic affected 3 million hectares of wheat in South America in the 1990s. In 1996, the first blast outbreak in Bolivia resulted in almost 80% production losses. In Paraguay, the first epidemic occurred in 2002, when production losses of over 70% were recorded. In Brazil, losses due to wheat blast occurred in 2009 and 2012, when damage above 40% compromised crops in their wheat heading stage in Paraná, Mato Grosso do Sul and São Paulo. In the following years, the incidence of blast has also increased in the southern states of Brazil, with frequent records in Rio Grande do Sul and central-southern Paraná. In Argentina, the world’s 10th largest wheat producer, blast appeared in 2007 in crops in the north of the country, but it was in 2012, when it reached the province of Buenos Aires, Argentina's main wheat farming hub, that the disease raised the red alert. to the risk of crop losses. In 2023, the problem was recorded in Uruguay for the first time. In 2016, there was the first record of wheat blast outside South America: an epidemic of the disease in Bangladesh, a country in South Asia, with losses of over 30% in crops. In 2018 it appeared in crops in Zambia, in the middle-south of the African continent. |

Simulation models to assess disease impacts

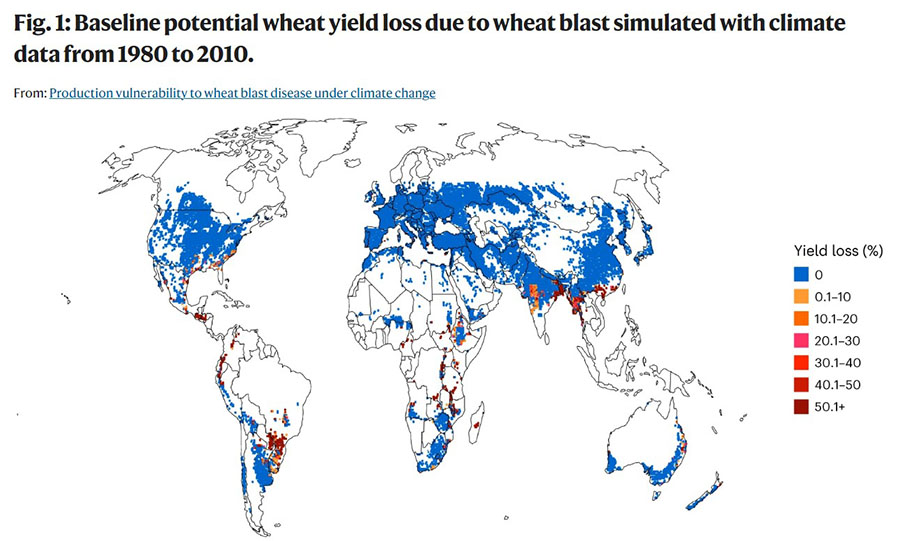

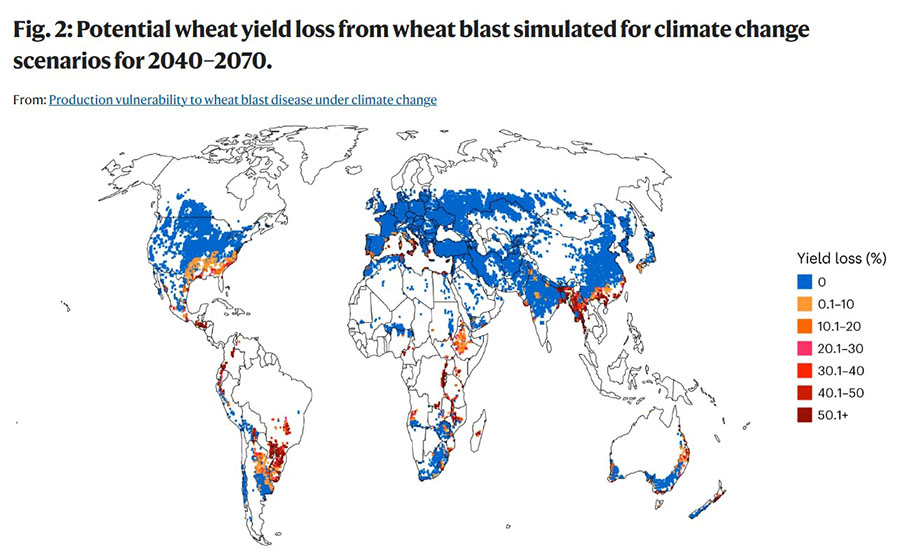

Based on future climate scenarios projected by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), researchers in the agronomic and computer sciences used modeling and simulation techniques to estimate the possible impacts of the spread of wheat blast to the different continents where wheat is cultivated considering an environment of climate change that favors the disease.

The researchers used the model DSSAT Nwheat, which was developed at the University of Florida with collaborative updating by several research centers around the world, analyzing variables such as temperature increases, relative humidity, and increased CO2 in the atmosphere. To estimate scenarios, they used historical data records from between 1980 and 2010 and projected climate change for the period from 2040 to 2070.

Blast can reach every continent

Climate change can boost wheat blast and have it reach every continent with the exception of Antarctica.

In South American countries where the problem already occurs, the wheat areas that are vulnerable to the disease would increase from 13% to 30%. Projections indicate the risk of the disease reaching wheat crops in the United States, Mexico and Uruguay (Americas); Italy, Spain and France (Europe); Japan and southern China (Asia); Ethiopia, Kenya and Congo (Africa); New Zealand and western Australia (Oceania).

“Although environmental conditions in the Northern Hemisphere have not been favorable to blast yet, in a scenario of increased temperatures and humidity, the incidence of the disease in wheat crops is likely, especially in regions that are close to the Mediterranean Sea. Likewise, in southern China, where wheat cultivation has grown in recent years”, explains University of Florida professor Willington Pavan.

Under current conditions, blast already poses a threat to 6.4 million hectares of wheat in the world. In a climate change scenario, by around 2050, the disease could affect 13.5 million hectares, resulting in a 13% reduction in global wheat production, with losses that could reach 69 million tons of wheat per year.

“There are several initiatives in the world trying to contain the disease (plant breeding, biotechnology, chemical control strategies and crop management, for instance), but we have not yet achieved full success in eradicating the problem of wheat blast. Resilience to climate change requires preparation based on projections to inform decision-making to minimize losses from wheat blast and ensure the planet's food security”, Fernandes concludes.

Scientific publicationThe paper “Production vulnerability to wheat blast disease under climate change” was published on Nature Climate Change. The publication organized by CIMMYT brought together researchers from Brazil, the United States, Mexico, Germany and Bangladesh. |

Joseani M. Antunes (MTb 9.396/RS)

Embrapa Wheat

Press inquiries

trigo.imprensa@embrapa.br

Translation: Mariana Medeiros (13044/DF)

Embrapa's Superintendency of Communications

Further information on the topic

Citizen Attention Service (SAC)

www.embrapa.br/contact-us/sac/