New version of the history of maize based on genetic and archaeological evidence

New version of the history of maize based on genetic and archaeological evidence

Photo: Fabio Oliveira Freitas

Multidisciplinary research rescues the history of maize, the result of breeding in the American continent

An international multidisciplinary team with scientists from 14 institutions proved for the first time that maize plants brought from Mexico to South America over 6,500 years ago were a more primitive genetic type than previously believed. The conclusions were based on genetic, archaeological and linguistic evidence. Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology (Brasília, DF, Brazil), the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History (Washington, DC, USA) and the University of Warwick (Coventry, UK) participated in the study.

The original research results are reported in the latest issue of the American journal Science, which will start circulating this Thursday (December 13), in a paper entitled “Multiproxy evidence highlights a complex evolutionary legacy of maize in South America”.

According to the results, the process of selection and domestication of the plant species had not been finished in Mexico by the time varieties started to spread out into South America, where maize took its final shape in the Southwestern Amazon region. That entails a review of the history of the domestication of one of the world's most important crops, revealing that Mexican and Southwestern Amazon farmers continued to improve the crop throughout thousands of years, until the plant was completely domesticated in those regions.

The scientists' report deepens the understanding of the different research areas regarding the history of maize at people's tables. “It is the evolutionary history of domesticated plants in the long term that has made them suitable for the today's human environment”, declares Logan Kistler, archaeogenomics and archaeobotany curator of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and main author of the study. According to him, understanding this history provides tools to assess the future of maize, while humankind continues to drastically modify the global environment in the attempt to increase harvests to meet the increasing demand for food in the planet.

From teosinte to maize

The research has revealed that the history of maize starts with its wild ancestor, called teosinte. According to the paper on Science, teosinte bears little resemblance to the maize that we know nowadays, since its ears are small and its few grains are protected by a practically impenetrable kind of covering. “In fact we were not able to clarify the reason why people were initially interested in teosinte, but we know that with time farmers performed selections and obtained plants with desirable traits, with bigger ears and softer, abundant grains, making it the crop that it is today”, Kistler comments.

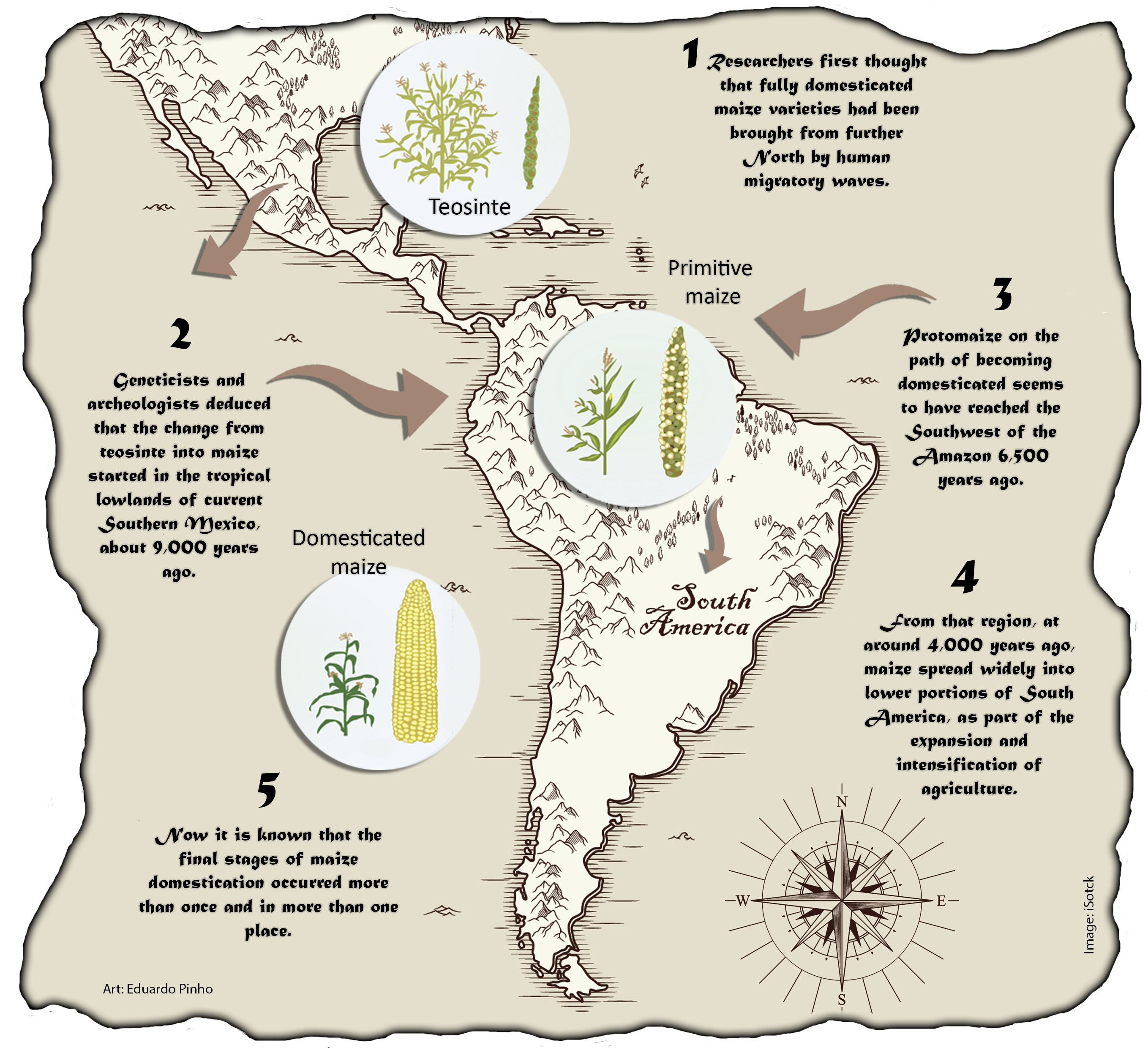

For years, geneticists and archaeologists deduced that the change from teosinte into maize had started in the tropical low lands of the South of Mexico about 9,000 years ago. The teosinte that grows naturally in the region is more genetically similar to the maize that we know today, while teosinte from other parts of Mexico and Central America is more distant from maize, despite both remaining apart from the domesticated plant by hundreds of genes.

Old pollen found in sediments

The paper also reports that in the southwest of the Amazon and the coast of Peru, microscopical pollen and other remaining portions of plant parts that resisted time were found in old sediments, indicating that the history of the use of the fully domesticated maize is about 6,500 years old. Hence the researchers at first thought that fully domesticated maize varieties had been brought from further North by human migration waves. “Thus, before we started conducting this study, it seemed that there had only been one domestication event in Mexico, and that people had spread out an already totally domesticated type of maize into the South ”, comments Logan Kistler.

However, a few years ago, when geneticists sequenced the DNA of the 5,000-year old maize found in Mexico, history got more complicated. The genetic results showed that they found a protomaize (a maize that is at a genetic stage between the wild and the domesticated variety) and that its genes were a mix between those found in teosinte and those found in the domesticated plant.

Nevertheless, the archaeological DNA determined that this ancestral plant did not have hard covering in each kernel like teosinte did, but a single husk leaf involving the cob, like maize, despite not having acquired other characteristics that made maize a widely known culture yet.

That posed a mystery to scientists and, to solve it, the team coordinated by Kistler reconstructed the plant's evolution. For this purpose, they made a genetic comparison of more than 100 varieties of modern maize that grow in all of the Americas, including 40 newly sequenced varieties - many from the low lands of the South America, which had been sub-represented in previous studies.

Embrapa's gene bank and traditional peoples helped in the solution

Many of such old varieties were collected in collaboration with indigenous and traditional farmers throughout decades, and stored at Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology's Gene Bank.

The Embrapa researcher Fabio Oliveira Freitas reports that this work of conserving traditional plant varieties cultivated by Indians in the South border of the Amazon rainforest helped to guide the discussion about how the propagation of maize may have occurred in the past. The genomes of 11 archaeological plants, including nine recently sequenced samples, inclusing some found in caves in the north of Minas Gerais state, were also part of the analysis.

The teams mapped the genetic relationships between the plants and discovered distinct lineages, each with its own level of similarity with their common ancestor, teosinte. For the scientists, the final stages of maize domestication occurred more than once and in more than a single place. “The results show that maize does not have a simple history and that the crop was not formed the way we had learned”, states Robiyn Allaby, a researcher from the University of Warwick.

The scientists say that at the beginning of the study the genetic data found were intriguing; as the many collaborators started to integrate the data with their knowledge regarding the history of South America, the picture of how maize could have spread out into the continent started to be elucidated.

Thus, a protomaize on the path of becoming domesticated seems to have reached South America at least twice, Kistler says. About 6,500 years ago, the partially domesticated plant arrived at the Southwestern portion of the Amazon, which was already an area where other species were being domesticated, as rice, cassava and other crops were cultivated. The plant was probably adopted as part of local agriculture and continued to evolve under human influence until it became a completely domesticated crop later.

From that region, domesticated maize moved to the East of the Amazon as part of an expansion and intensification of agriculture that archaeologists had already noticed in that area. Around 4,000 years ago, maize spread widely into the low lands of South America. There is genetic, linguistic and archaeological evidence that maize cultivation grew East a second time, from the Andes towards the Atlantic, about a thousand years ago.

For the Embrapa scientist, these results enhance the importance of past and present indigenous populations in the selection, maintenance and diffusion of cultivated plants, and he underscores the complementarity of the ex situ conservation (in gene banks like Embrapa's) and in-situ on-farm conservation performed by traditional farmers. “In the first case, there are long run assurances; in the second, the live evolutionary process goes on with all the cultural aspects that are inherent to each human group”, Freitas details.

Translation: Mariana Medeiros.

Maria Devanir Heberlê (MTb 5297/RS)

Embrapa Genetic Resources and Biotechnology

Press inquiries

recursos-geneticos-e-biotecnologia.imprensa@embrapa.br

Phone number: +55 61 3448-3266

Further information on the topic

Citizen Attention Service (SAC)

www.embrapa.br/contact-us/sac/