Studies have shown that winter cereals can replace corn in swine and poultry feed. The aim is to reduce dependence on corn as an ingredient in feeds and concentrates, whose production is not enough to meed demand in Southern Brazil. The research paves the way to broaden the market for winter cereals, considered below the local potential. Findings show that wheat and triticale are the cereals with higher potential to replace corn. Studies have also assessed barley. Cereals can be cultivated in lands that remain idle for the winter in the South of the country. Research carried out by Embrapa Wheat and Embrapa Swine and Poultry has found that winter cereals such as wheat, oats, rye, barley and triticale are viable options to replace corn in the formulation of feeds and concentrates to feed pigs and poultry. In addition to reducing dependence on this grain in the Brazilian South, whose production has not been enough to meet demand, the finding expands the market for winter cereals, which occupy about 20% of the potential cultivation area. The scarcity of corn as opposed to the growing increase in the production of animal protein and to the idleness of production areas in the local winter were the main motivations for the studies, which assess the economic and nutritional viability of the use of winter cereals in the composition of feed, as well as cultivars that most suit pig and poultry nutrition. The idle areas in the winter in Southern Brazil, especially in Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul states, are estimated at more than 6 million hectares, considering spaces in fallow or with cover plants. Taking better advantage of the local winter to supply the animal protein market is the project that Embrapa is developing in the region, in partnership with various segments of the production sector, industry and public authorities. Consumption Each Brazilian consumes an average of 43 kg of chicken and 15 kg of pork per year. To meet this demand, it is necessary to produce around 30 million tons of grains like corn, wheat, soybeans, and others. Corn deficit increases spending and worries farmers Corn production in Brazil reached 100 million tons in the 2019 harvest. Out of this volume, 43 million tons are exported and another 4.5 million tons are aimed at ethanol production. And out of the total of grains destined for domestic consumption, more than half are used for animal feed. Figure 1– Balance of corn production and consumption in Brazilian municipalities in 2019 and the current and future water and rail transportation mix in Brazil. Source: Santos Filho et al., 2020. In 2019, the South of Brazil produced 25 million tons of corn, an increase of 44% compared to the volumes achieved in the 2000s. With the exception of Paraná, which is reinforced by safrinha or second crop corn, the remaining Southern states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul have approximately half of the corn they consume available (considering production minus exports). Just to meet the demand from the animal protein industry, which last year accounted for a production of 2.7 million tons of pigs and almost eight million tons of chicken, 21.5 million tons of corn were needed. The corn deficit in the South Region is supplied by grains brought from the midwest of Brazil, with logistic costs that overload production. Figure 2 – Difference between areas with annual summer crops and winter crops in cities of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. Source: Santos Filho et al., 2020. The following table shows how corn production has accompanied the growth in pig and poultry production in the South: Wheat and triticale are the best candidates to replace corn Embrapa's research especially points to wheat and triticale as energy foods with the potential to replace corn and soybean meal in diets for pigs and broilers, provided that adjustments are made to aminoacids and energy levels to meet the requirements of the animals at every stage of development. “With nutritional value that supplements corn and soybean meal, these cereals are technically and economically viable for inclusion in pig and poultry diets, and can supply a significant part of the demand for grains for these two species,” remarks the Embrapa researcher Teresinha Bertol. Initial results show that the nutritional values for those cereals are variable, depending on the cultivar, the place and year of production. Therefore, it is essential to assess each batch of these raw materials before using them to produce feed. One of the cultivars that showed good potential for feed composition was the BRS Tarumã, wheat, which has higher values of crude protein and metabolizable energy. “With a protein content close to 18%, this wheat was developed for animal feed in an alternative market to bread making, and has been used for more than 20 years in cattle breeding, now with the possibility to also meet the demand for pigs and birds,” explains researcher Eduardo Caierão, breeder at Embrapa Wheat. According to him, the cultivar has excellent energy value, very close to soybean meal, which also allows lower costs in this production item. Other wheat varieties like BRS Pastoreio and BRS Sanhaço, as well as the triticale cultivars BRS Saturno and Embrapa 53, had lower energy content, which increases the demand for oil in the feed. “The use of these cereals can be economically more advantageous in the stages when the animals present lower energy requirements, e.g. the gestation of the pigs. In the case of BRS Tarumã wheat, due to its higher energy content than corn and high protein content, the use is more productive in the growth and termination stages, when the demand for these factors is higher,” explains the researcher of the Embrapa Swine and Poultry Jonas dos Santos Filho. Photos: Eduardo Caierão (wheat) and Alfredo do Nascimento Júnior (triticale seeds) Barley is also part of the studies According to nutritional assessments, the optimal levels for the inclusion of wheat and triticale in the pig diet are around 35%, while for barley these levels are between 20% and 25% from the growth stage. In the case of broilers and laying hens, levels of 20% to 30% of wheat or triticale inclusion are recommended, and up to 20% of barley in the feed from the initial stage. According to Teresinha Bertol, these are the levels that allow the best combination of ingredients to optimize the balance of essential amino acids and that provide the best pellet quality (pelleted feed format). However, she points out that it is possible to completely replace corn with wheat or triticale in pig diets, as long as the necessary adjustments are made to the nutritional levels to meet the requirements of the animals at each stage. Industry's closer ties with the production sector The use of winter cereals in the production of animal protein is nothing new, but the mobilization that brought together specialists, entities representing the production sector and public authorities aim to provide greater security in grain growers' yield and in ensuring raw materials to the supply industry. With the objective of increasing the area with winter crops, the government of the state of Santa Catarina - which is the largest corn importer in Brazil - launched, in the beginning of this year, in February 2020, the “Incentive Program for the Planting of Grains of Winter,” which is encouraging farmers to invest in winter cereals with the potential to compose the matrix of ingredients for pig and poultry feed. The program has the technical support of research institutions such as Embrapa and Epagri/SC, the supply of inputs and technical assistance from the cooperative sector and the acquisition of grains by the pork and poultry industry. One of the challenges to ensure the supply of animal protein industry with winter cereals is the not always favorable climate, responsible for many frustrated crops in winter with rains in the pre-harvest that can result in loss of grain quality and even contamination by mycotoxins, causing fungi that cause complications in the animals' digestive system. But for the agricultural expert of Seara's nutrition team, Herbert Rech, the agroindustry already has experience to adapt to the adverse moment: “Problems with crop frustration that affect the nutritional or sanitary quality of grains also occur in corn and other crops. cultures. It is up to the industry to know how to make nutritional adjustments to maintain the animals' performance.” According to him, winter cereals need to compete nutritionally and financially with the other ingredients of the feed, such as corn and soybean meal, but without losing in quality: “It is important to evaluate that we are not talking about using the waste from grain production to animal feed. We need quality wheat, which meets the demand of the animal protein industry and not only punctual offers of grains that did not meet the requirements of bread making.” Rech points out that “if the producer uses wheat with characteristics of interest for animal feed, such as greater energy, proteins and less fiber, it will obviously compete better with other commodities. Quality wheat is valued in any market, but it is necessary to study every opportunity.” “There are no technical doubts about the use of winter cereals to feed pigs and poultry. What is under discussion now is the business model to make planting and use in feed possible,” confirms Alexandre Gomes da Rocha, from Aurora Alimentos. He defends the establishment of an indexation of the price of winter cereals to the price of corn: “With the pre-fixed price there will be a loss for one side. If the price of corn is low, the agribusiness loses by paying dearly for winter cereals; and in the opposite scenario, the producer loses the opportunity for a better price of wheat. In the event of successive losses to one side, the business tends to lose strength and discontinue. That is why there is a need for a clear, pre-defined model that provides security for both sides.” In the South Region, the negotiations of the animal protein industry with the productive sector have already started, initially with large producers and cooperatives, but they should expand the reach to small producers, mainly those that operate close to the industries. Photo: Lucas Scherer Representatives from animal protein research and industry discuss the opportunities and challenges for the use of winter cereals in swine and poultry diets. In memoriam One of the study participants, researcher Jonas Irineu dos Santos Filho, passed away on October 8 at the age of 56. Read more about him here.

Photo: Lucas Scherer

The research findings expands the market for winter cereals, which occupy about 20% of the potential cultivation area and can be alternatives in the formulation of feed for swine and poultry.

-

Studies have shown that winter cereals can replace corn in swine and poultry feed. -

The aim is to reduce dependence on corn as an ingredient in feeds and concentrates, whose production is not enough to meed demand in Southern Brazil. -

The research paves the way to broaden the market for winter cereals, considered below the local potential. -

Findings show that wheat and triticale are the cereals with higher potential to replace corn. Studies have also assessed barley. -

Cereals can be cultivated in lands that remain idle for the winter in the South of the country. |

Research carried out by Embrapa Wheat and Embrapa Swine and Poultry has found that winter cereals such as wheat, oats, rye, barley and triticale are viable options to replace corn in the formulation of feeds and concentrates to feed pigs and poultry. In addition to reducing dependence on this grain in the Brazilian South, whose production has not been enough to meet demand, the finding expands the market for winter cereals, which occupy about 20% of the potential cultivation area.

The scarcity of corn as opposed to the growing increase in the production of animal protein and to the idleness of production areas in the local winter were the main motivations for the studies, which assess the economic and nutritional viability of the use of winter cereals in the composition of feed, as well as cultivars that most suit pig and poultry nutrition.

The idle areas in the winter in Southern Brazil, especially in Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul states, are estimated at more than 6 million hectares, considering spaces in fallow or with cover plants. Taking better advantage of the local winter to supply the animal protein market is the project that Embrapa is developing in the region, in partnership with various segments of the production sector, industry and public authorities.

Consumption Each Brazilian consumes an average of 43 kg of chicken and 15 kg of pork per year. To meet this demand, it is necessary to produce around 30 million tons of grains like corn, wheat, soybeans, and others. |

Corn deficit increases spending and worries farmers

Corn production in Brazil reached 100 million tons in the 2019 harvest. Out of this volume, 43 million tons are exported and another 4.5 million tons are aimed at ethanol production. And out of the total of grains destined for domestic consumption, more than half are used for animal feed.

Figure 1– Balance of corn production and consumption in Brazilian municipalities in 2019 and the current and future water and rail transportation mix in Brazil. Source: Santos Filho et al., 2020.

In 2019, the South of Brazil produced 25 million tons of corn, an increase of 44% compared to the volumes achieved in the 2000s. With the exception of Paraná, which is reinforced by safrinha or second crop corn, the remaining Southern states of Santa Catarina and Rio Grande do Sul have approximately half of the corn they consume available (considering production minus exports).

Just to meet the demand from the animal protein industry, which last year accounted for a production of 2.7 million tons of pigs and almost eight million tons of chicken, 21.5 million tons of corn were needed. The corn deficit in the South Region is supplied by grains brought from the midwest of Brazil, with logistic costs that overload production.

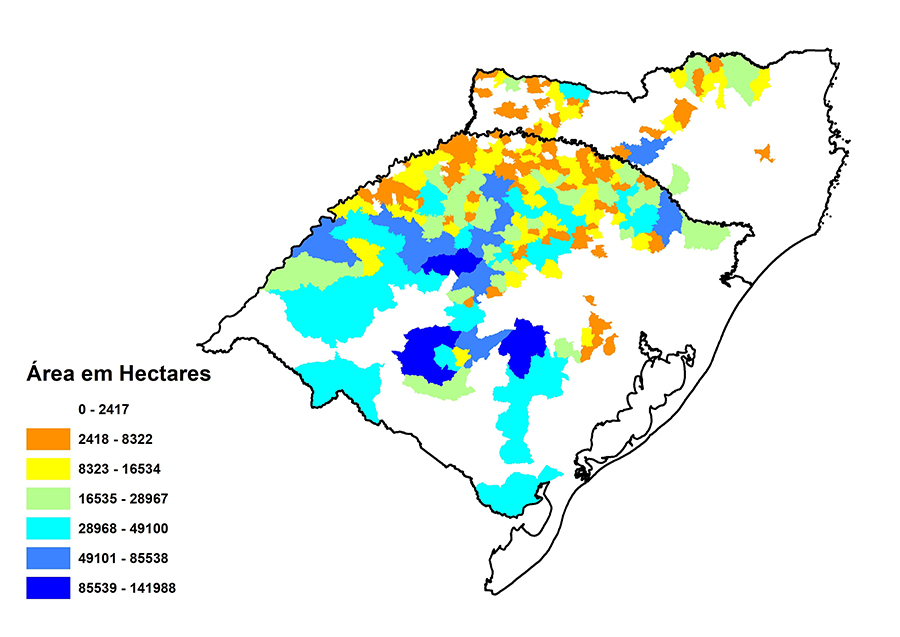

Figure 2 – Difference between areas with annual summer crops and winter crops in cities of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. Source: Santos Filho et al., 2020.

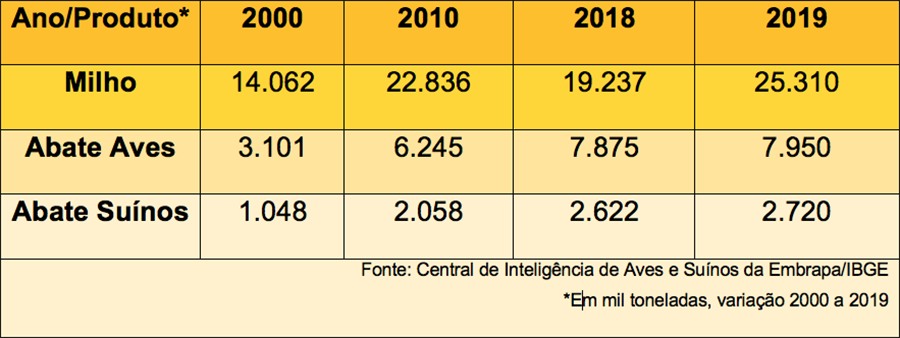

The following table shows how corn production has accompanied the growth in pig and poultry production in the South:

Wheat and triticale are the best candidates to replace corn Wheat and triticale are the best candidates to replace corn

Embrapa's research especially points to wheat and triticale as energy foods with the potential to replace corn and soybean meal in diets for pigs and broilers, provided that adjustments are made to aminoacids and energy levels to meet the requirements of the animals at every stage of development. “With nutritional value that supplements corn and soybean meal, these cereals are technically and economically viable for inclusion in pig and poultry diets, and can supply a significant part of the demand for grains for these two species,” remarks the Embrapa researcher Teresinha Bertol. Initial results show that the nutritional values for those cereals are variable, depending on the cultivar, the place and year of production. Therefore, it is essential to assess each batch of these raw materials before using them to produce feed.  One of the cultivars that showed good potential for feed composition was the BRS Tarumã, wheat, which has higher values of crude protein and metabolizable energy. “With a protein content close to 18%, this wheat was developed for animal feed in an alternative market to bread making, and has been used for more than 20 years in cattle breeding, now with the possibility to also meet the demand for pigs and birds,” explains researcher Eduardo Caierão, breeder at Embrapa Wheat. According to him, the cultivar has excellent energy value, very close to soybean meal, which also allows lower costs in this production item. One of the cultivars that showed good potential for feed composition was the BRS Tarumã, wheat, which has higher values of crude protein and metabolizable energy. “With a protein content close to 18%, this wheat was developed for animal feed in an alternative market to bread making, and has been used for more than 20 years in cattle breeding, now with the possibility to also meet the demand for pigs and birds,” explains researcher Eduardo Caierão, breeder at Embrapa Wheat. According to him, the cultivar has excellent energy value, very close to soybean meal, which also allows lower costs in this production item.

Other wheat varieties like BRS Pastoreio and BRS Sanhaço, as well as the triticale cultivars BRS Saturno and Embrapa 53, had lower energy content, which increases the demand for oil in the feed. “The use of these cereals can be economically more advantageous in the stages when the animals present lower energy requirements, e.g. the gestation of the pigs. In the case of BRS Tarumã wheat, due to its higher energy content than corn and high protein content, the use is more productive in the growth and termination stages, when the demand for these factors is higher,” explains the researcher of the Embrapa Swine and Poultry Jonas dos Santos Filho. Photos: Eduardo Caierão (wheat) and Alfredo do Nascimento Júnior (triticale seeds) |

Barley is also part of the studies

According to nutritional assessments, the optimal levels for the inclusion of wheat and triticale in the pig diet are around 35%, while for barley these levels are between 20% and 25% from the growth stage. In the case of broilers and laying hens, levels of 20% to 30% of wheat or triticale inclusion are recommended, and up to 20% of barley in the feed from the initial stage.

According to Teresinha Bertol, these are the levels that allow the best combination of ingredients to optimize the balance of essential amino acids and that provide the best pellet quality (pelleted feed format). However, she points out that it is possible to completely replace corn with wheat or triticale in pig diets, as long as the necessary adjustments are made to the nutritional levels to meet the requirements of the animals at each stage.

Industry's closer ties with the production sector

The use of winter cereals in the production of animal protein is nothing new, but the mobilization that brought together specialists, entities representing the production sector and public authorities aim to provide greater security in grain growers' yield and in ensuring raw materials to the supply industry.

With the objective of increasing the area with winter crops, the government of the state of Santa Catarina - which is the largest corn importer in Brazil - launched, in the beginning of this year, in February 2020, the “Incentive Program for the Planting of Grains of Winter,” which is encouraging farmers to invest in winter cereals with the potential to compose the matrix of ingredients for pig and poultry feed. The program has the technical support of research institutions such as Embrapa and Epagri/SC, the supply of inputs and technical assistance from the cooperative sector and the acquisition of grains by the pork and poultry industry.

One of the challenges to ensure the supply of animal protein industry with winter cereals is the not always favorable climate, responsible for many frustrated crops in winter with rains in the pre-harvest that can result in loss of grain quality and even contamination by mycotoxins, causing fungi that cause complications in the animals' digestive system. But for the agricultural expert of Seara's nutrition team, Herbert Rech, the agroindustry already has experience to adapt to the adverse moment: “Problems with crop frustration that affect the nutritional or sanitary quality of grains also occur in corn and other crops. cultures. It is up to the industry to know how to make nutritional adjustments to maintain the animals' performance.”

According to him, winter cereals need to compete nutritionally and financially with the other ingredients of the feed, such as corn and soybean meal, but without losing in quality: “It is important to evaluate that we are not talking about using the waste from grain production to animal feed. We need quality wheat, which meets the demand of the animal protein industry and not only punctual offers of grains that did not meet the requirements of bread making.”

Rech points out that “if the producer uses wheat with characteristics of interest for animal feed, such as greater energy, proteins and less fiber, it will obviously compete better with other commodities. Quality wheat is valued in any market, but it is necessary to study every opportunity.”

“There are no technical doubts about the use of winter cereals to feed pigs and poultry. What is under discussion now is the business model to make planting and use in feed possible,” confirms Alexandre Gomes da Rocha, from Aurora Alimentos.

He defends the establishment of an indexation of the price of winter cereals to the price of corn: “With the pre-fixed price there will be a loss for one side. If the price of corn is low, the agribusiness loses by paying dearly for winter cereals; and in the opposite scenario, the producer loses the opportunity for a better price of wheat. In the event of successive losses to one side, the business tends to lose strength and discontinue. That is why there is a need for a clear, pre-defined model that provides security for both sides.”

In the South Region, the negotiations of the animal protein industry with the productive sector have already started, initially with large producers and cooperatives, but they should expand the reach to small producers, mainly those that operate close to the industries.

Photo: Lucas Scherer

Representatives from animal protein research and industry discuss the opportunities and challenges for the use of winter cereals in swine and poultry diets.

Joseani M. Antunes (MTb 9396/RS)

Embrapa Wheat

Press inquiries

trigo.imprensa@embrapa.br

Lucas Scherer Cardoso (MTb 10.158/RS)

Embrapa Swine and Poultry

Press inquiries

suinos-e-aves.imprensa@embrapa.br

Further information on the topic

Citizen Attention Service (SAC)

www.embrapa.br/contact-us/sac/